Each fall, the first year medical students at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine are asked to create an art project for their “Doctor/Patient Relationship” course. The students are assigned to reflect on what this relationship means and to both depict it and write a reflection about it. It’s from these pieces that we at MSRJ select our cover photos for each issue. There are so many amazing projects each year that we are unable to accommodate each one as a cover. We want to showcase these pieces to you. Below are some of these pieces.

Human Medicine are asked to create an art project for their “Doctor/Patient Relationship” course. The students are assigned to reflect on what this relationship means and to both depict it and write a reflection about it. It’s from these pieces that we at MSRJ select our cover photos for each issue. There are so many amazing projects each year that we are unable to accommodate each one as a cover. We want to showcase these pieces to you. Below are some of these pieces.

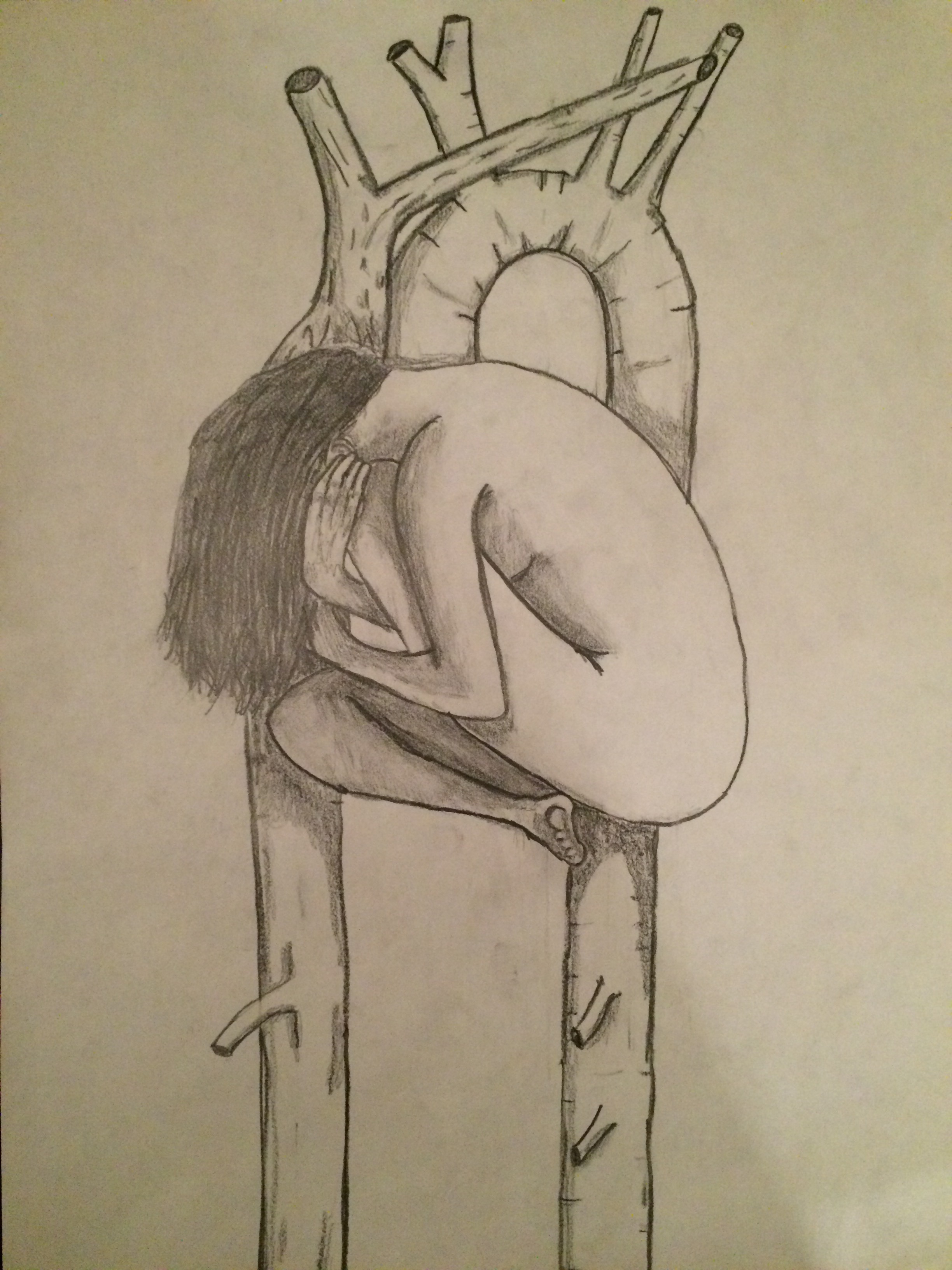

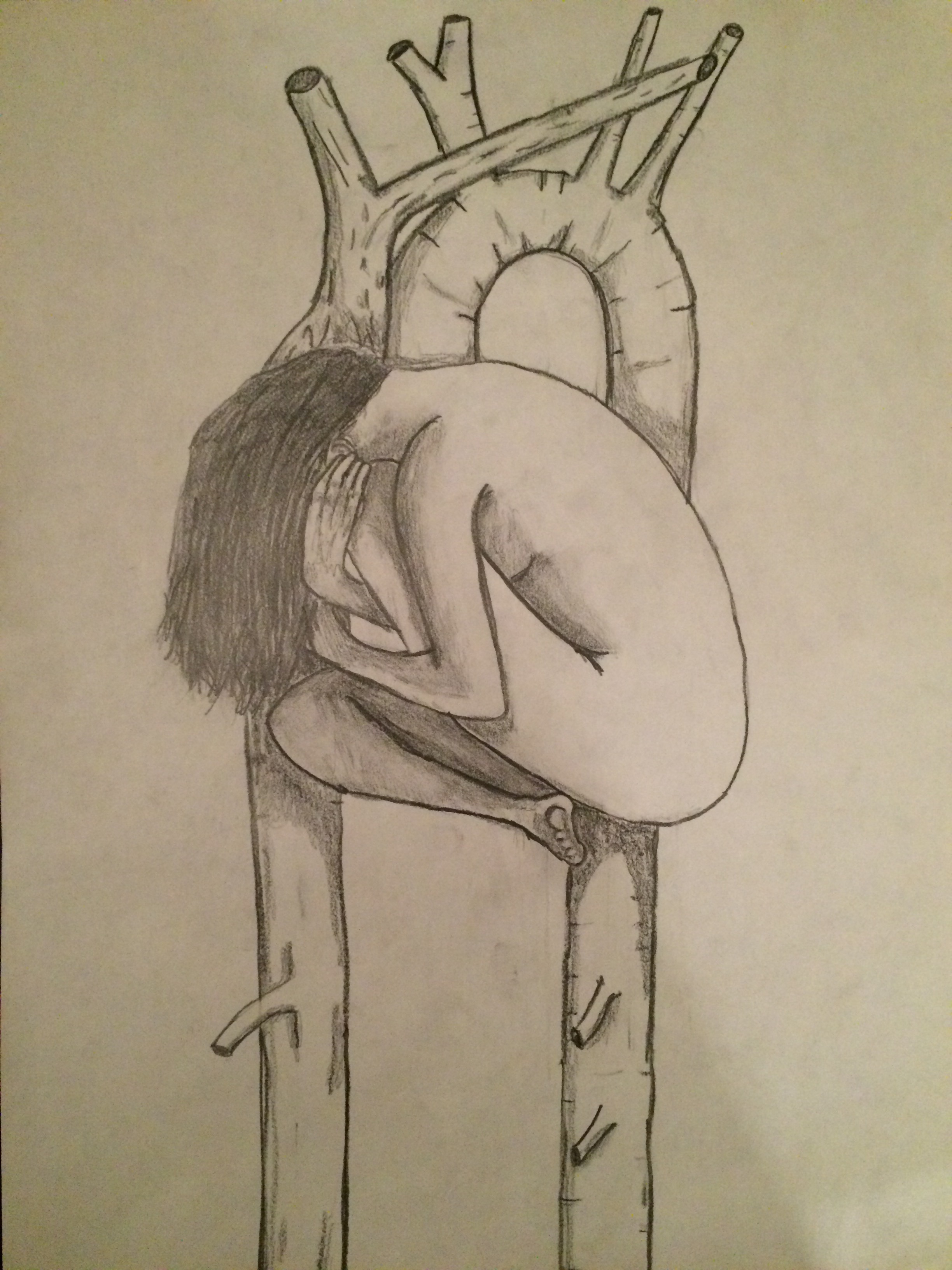

Created by: Jeremiah Reenders

Created by: Jeremiah Reenders

When I started reflecting on the relationship between physicians and patients, I thought about the role of physicians and the function they serve for humanity. The long, arduous process of evolution has brought about infinitely complex, stunningly intricate, and beautifully balanced

and the function they serve for humanity. The long, arduous process of evolution has brought about infinitely complex, stunningly intricate, and beautifully balanced biological machinery that serves as the body in which we both perceive and interact with the universe around us. As impressive as our bodies are, however, there will always be enemies trying to hijack it, and innate imperfections that require the skill and wisdom of a healer to defend and restore our physical state. At first glance, it seems that this basic premise of our existence describes the role of physicians

biological machinery that serves as the body in which we both perceive and interact with the universe around us. As impressive as our bodies are, however, there will always be enemies trying to hijack it, and innate imperfections that require the skill and wisdom of a healer to defend and restore our physical state. At first glance, it seems that this basic premise of our existence describes the role of physicians : to heal our bodies. Upon deeper reflection however, I couldn’t come to accept such a simplistic claim.

: to heal our bodies. Upon deeper reflection however, I couldn’t come to accept such a simplistic claim.

Somewhere in the course of our species’ existence, something was added that set us apart. The soul became entangled in every muscle fiber and between every neuron. Our existence became more than just the air entering and exiting our lungs and the blood that supplied our flesh. It transcended the physical and formed a connection between the human head, full of instinct and logic, and the heart, which breathes feeling in to an otherwise emotionless dimension. Although this connection is somewhat imperfect, it comprises the very core of who we are. It is impossible to tease apart the physical from the emotional, the mental from the chemical, the person and the flesh they live in. With my piece, I wanted to portray this fatal relationship. The heart of a person is a person. A physician should recognize that this person is far more complex than their anatomy and biochemistry. He/she should be prepared to look past his/her beliefs, values, and principles, and see only the person that exists before them. The patient is as much their soul as they are their body, and a physician must treat both.

should recognize that this person is far more complex than their anatomy and biochemistry. He/she should be prepared to look past his/her beliefs, values, and principles, and see only the person that exists before them. The patient is as much their soul as they are their body, and a physician must treat both.

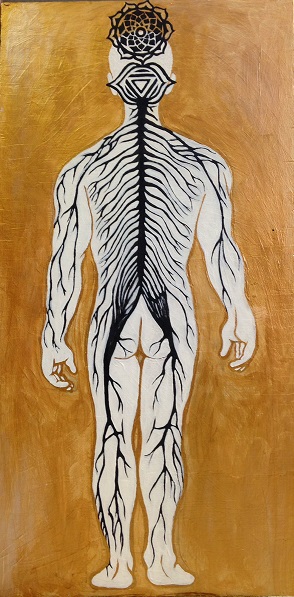

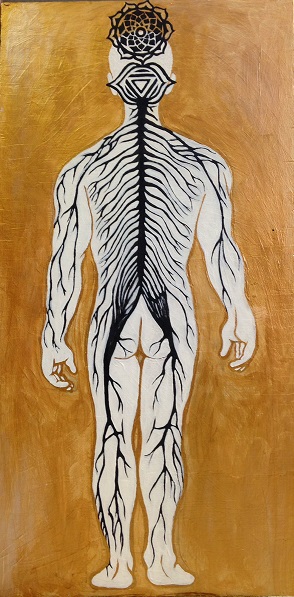

Created by: Irene Warner

Created by: Irene Warner

For my Mid-Term Reflective Project, I decided to explore the concept of mindbody connection. While it may be tempting to reduce medicine to biochemical pathways and pure science, human beings are more complicated than the sum of their parts. When interacting with patients, it is important to remember that they are not only made up of quantifiable physical components, but of intangible spiritual and cultural components as well. My painting depicts a human nervous system fused with the Ajna (third-eye chakra) and the Sahasrara (crown chakra). The color gold in the background symbolizes perfection and balance , like the “golden mean” described by Aristotle in his philosophical teachings.

, like the “golden mean” described by Aristotle in his philosophical teachings.

The nervous system is an essential part of human anatomy that coordinates all of the body’s function and sustains life. However, the concept of consciousness cannot be explained by nerves and synapses alone. In Hindu beliefs, the Ajna represents perception, intuition, and imagination. The Sahasrara is located at the crown of the head and represents higher consciousness, spirituality and wisdom. In my painting, the fusion of these symbols with the spinal cord and peripheral nervous system illustrates how the mind (i.e. higher consciousness and awareness) and physical body are extricably linked.

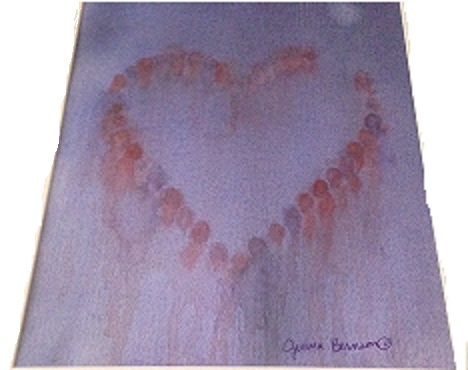

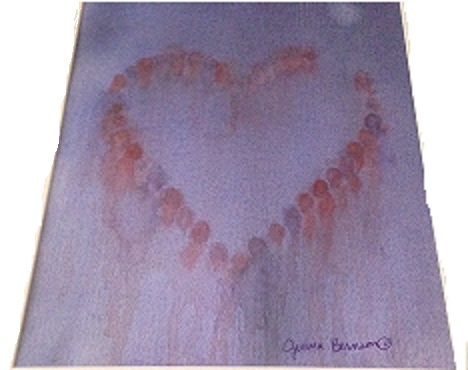

“Heart of Patient Compassion” Created by: Jenna Bernson

Created by: Jenna Bernson

I want to bring compassion to the patient-physician relationship. Compassion is represented by the heart shape as well as by the use of the color red. The heart, symbolic of my heart, is formed by abstract figures which stand for my patients. Notice that the heart is not complete, there is a portion left open. This represents always leaving an open heart to care for more patients. The background is done in purple, a cool color. This represents a sense of calmness I want to have and to give to my patients despite the fact that they may be going through very turbulent times or even though outside of our relationship, the world may be bleak (as represented by the starkness of the purple background). The figures are shown in both red and purple and every color in between, representing an openness of the heart also for diversity and inclusion. Culture influences so much of a person, from their daily activities to their approach to healthcare. So, understanding a patient’s values and culture is integral for a good patient-physician relationship. The differing perspectives and viewpoints of the patients is symbolized by the fact that every figure is given a different place in the heart. Each figure would see something slightly different even though they are all part of the same picture. Likewise, my own culture and values will influence the way in which I live and interact, even in my future practice. Therefore, I must be aware of my own background, beliefs and perspective to try to minimize and be aware of possible implicit biases. My perspective is represented by the use of abstract technique. Every person looking at this piece will pick out slightly different things that they see or will take away, which is undoubtedly different from what I see.

The Hospital Gown: Exploring the Patient-Physician Relationship Through Art and Metaphor

Created by: Carina Mendoza

Created by: Carina Mendoza

My project illustrates (through art) a typical patient, with a hospital gown covering the body like an inanimate protective barrier: shielding the host from an oblivious and, perhaps, indifferent external world. The hospital gown is symbolic of an anonymous person (in this case a female) who enters a physician’s office; the office of a healer who is also dressed in a gown (but a gown of identity, authority and distinction), and who may be unaware of the inherent role that the respective gowns play in the patient-physician relationship, or of the concerned heart that beats beneath the personal garments, veil of skin and cage of bones (the body) of the anonymous female. The hospital gown reminds me of several instructional and significant tenets of our profession as healers. First, I am reminded that it is our responsibility to remain patient-centered, to facilitate the patient-physician relationship, to remove any real or imagined inhibiting barriers created by the hospital gowns, and to establish a trustworthy, caring environment where the seemingly anonymous gown draped-person becomes a client, a patient with a name and feelings, and an individual with desires to be cared for as a deserving, respected and dignified human being. Second, I am reminded that as physicians we must resist any inclination to become oblivious, dismissive or disinterested in the role that gender, culture, religion and other non-physical factors play in the healing processes: we must, instead, remain cognizant of the connection between mind and body, of facial gestures and body language (ours and the patient’s); and about our own gender, cultural and religious biases that may obstruct our ability to remain empathic and sensitive to the plethora of insecurities that accompany pain and suffering. Third, I am reminded of the kindred human connection that we have with our patients, and that at some point in our lives we may experience a role reversal and become victims of disease and illness; yearning for the same sensitivity, compassion, consideration and understanding that we may be (unwittingly) denying our patients.

“RED Bond”

Created by: Abdelouahid Souala

Created by: Abdelouahid Souala

How can health care practitioners provide culturally competent care? Patients can present from a wide variety of backgrounds and cultures. Must we be aware of each culture’s customs in order to provide culturally competent care? I initially thought this is how cultural competence is practiced. However, I quickly realized that this is not feasible. Not only is there a great variety of cultures, but cultures evolve with time and new cultures and customs are formed frequently. The solution is quite simple, focus on the patient.

Each patient is unique. Culture is only one aspect of the patient. Nonetheless, it can be a very important aspect in some patients that helps guide their everyday life. Cultural competence is achieved by connecting with patients and asking about their cultural needs. Furthermore, collaboration with patient on how to meet these needs will help the provider incorporate specific interventions tailored to meet the patient’s cultural needs. Sometimes, these needs are easily met and are incorporated smoothly into the plan of care. Other times, these needs can be very challenging to meet. This is especially true when the cultural needs pose an obstacle to the planned care or are completely opposed to the standard medical treatment. This is one it’s most important to remember to keep the focus on the patient. If these challenging cultural needs are neglected with the intention of providing the scientifically deemed best therapy for the disease, then only the disease is being cared for and the rest of the patient is neglected. Sometimes this means that health care professionals must neglect the disease in order to care for the patient.

The painting is a great reminder of how to deliver culturally competent care. I made it to help remind me of cultural competence when I start practicing medicine. Healthcare professionals must act like the IV in the painting. Connect with the patient, identify their cultural needs, prepare a medical therapy that fulfills these needs, and finally deliver this personalized therapy to the patient.

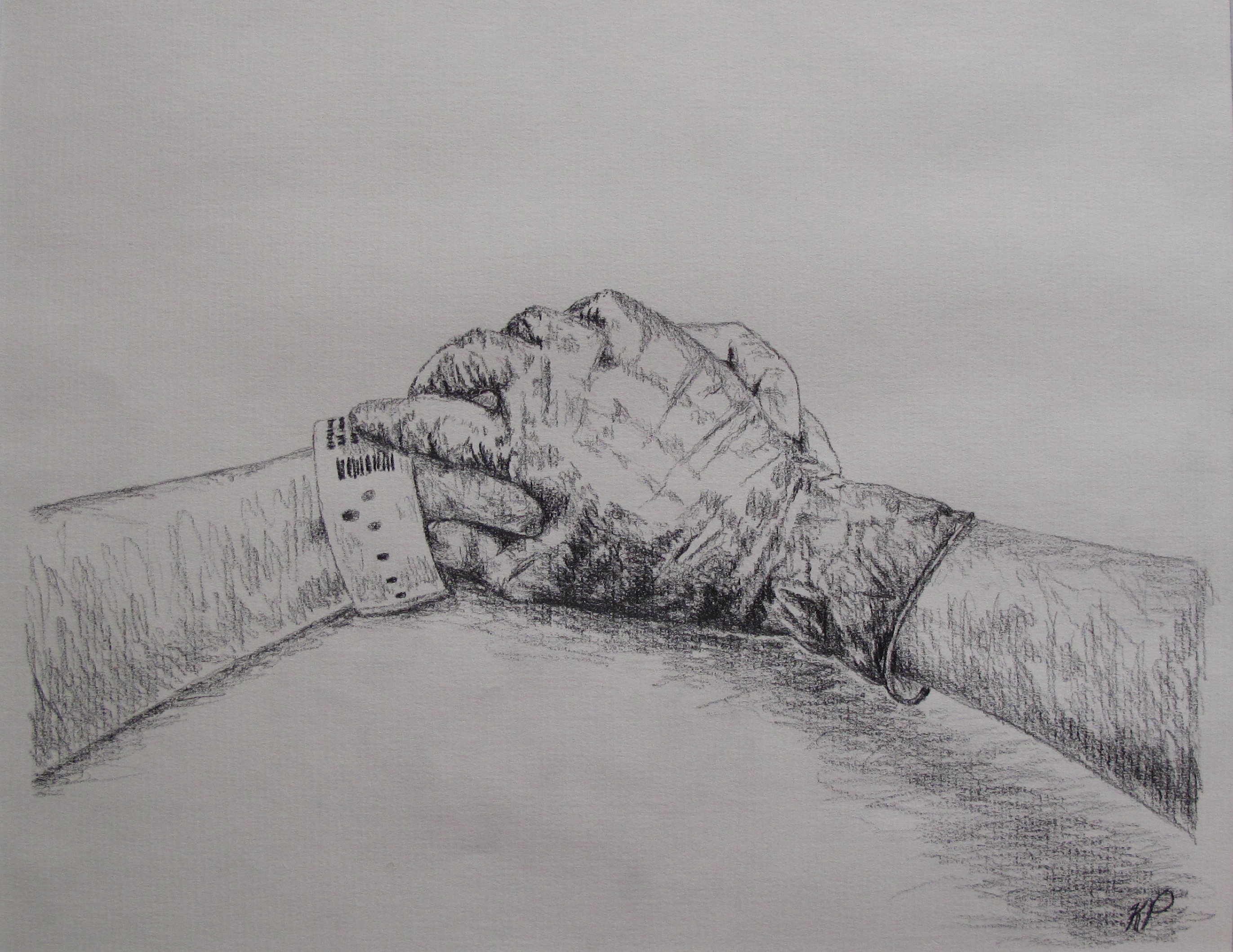

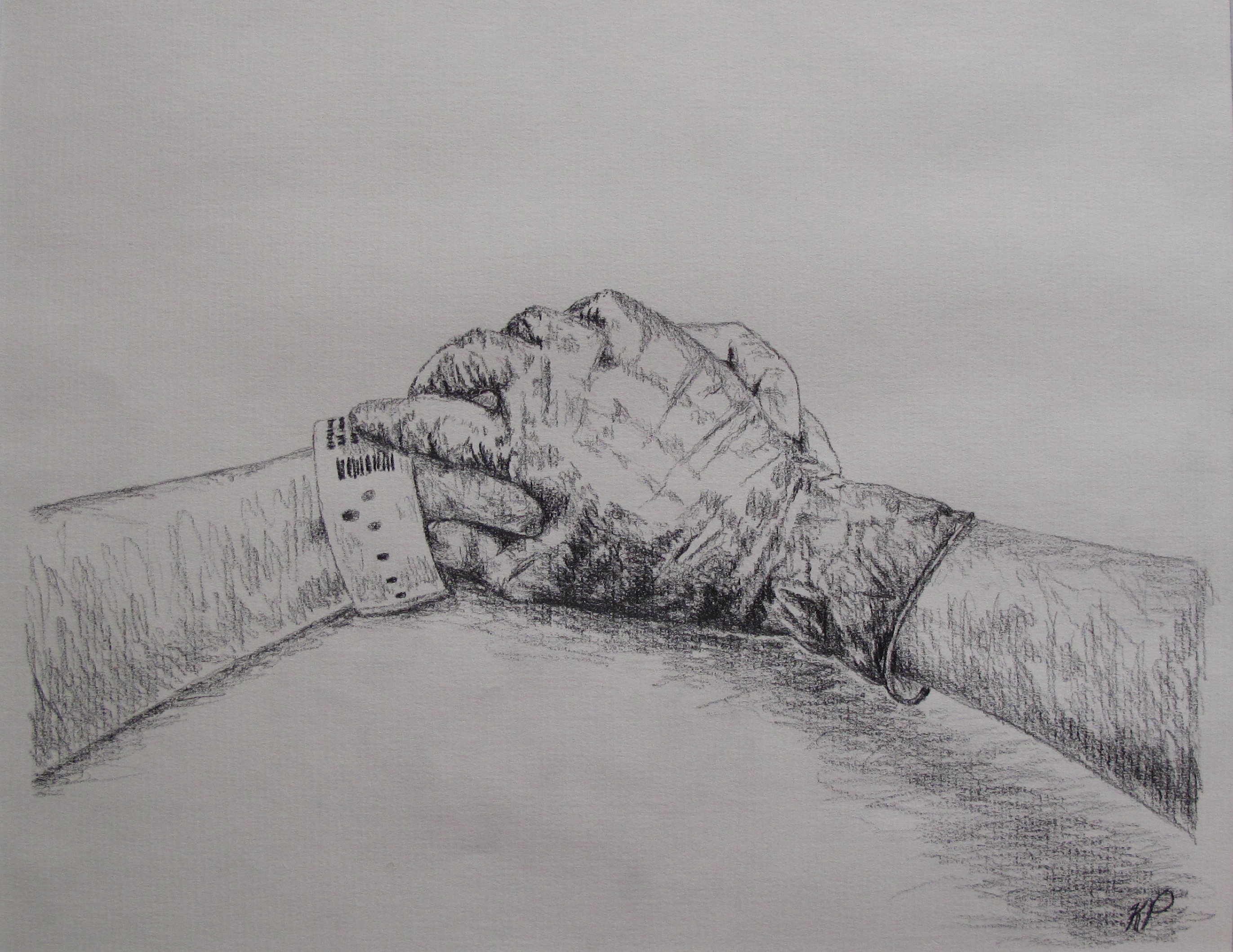

Created by: Kristina Priessnitz

Created by: Kristina Priessnitz

I can remember the intensity of her face as the operating room nurses wheeled the patient’s bed through the O.R. doors, her wide eyes haunting me even a year from now. I was a research assistant for Obstetric Anesthesiology, and I was upstairs in Labor and Delivery with my coworker to measure blood loss in C-section cases with our newly created calculation worksheet. Before we entered the room to follow the patient, our senior research supervisor and attending anesthesiologist took my coworker and me aside to talk in the hallway.

“You will not be measuring blood loss in this case, but just observing. This woman is here for a D&C; her baby had lethal genetic mutations and malformations,” she said. “Understandably she is quite upset. She wanted to have this baby.”

My mind was spinning. A D&C procedure, a dilation and curettage, was generally used in induced, therapeutic, or incomplete abortions and miscarriages. I could not imagine the turmoil and emotion that must have been coursing through the patient; I already caught a glimpse as she passed by earlier.

Walking into the O.R. behind the attending anesthesiologist, my coworker and I watched the nurses and doctors work in solemn silence. They carefully lifted her onto the operating table and gently laid her arms on the outstretched, horizontal armrests. As the anesthesiology residents worked to clip the blue drape curtain, and hook up patient monitors and IVs, I couldn’t help but watch the patient. Her eyes focused to the ceiling as she bit her lower lip, trying to control her expression. However, despite her effort, small clear tears slowly started to stream down her face sideways. So desperately, I wanted to reach out to her and comfort her, but my coworker and I were supposed to be flies on the wall—no touching the patient. Then the attending anesthesiologist did something I will never forget: she walked around the table to face the patient, ignoring the residents working above the patient’s head. The attending clasped the patient’s hand with her gloved hand and murmured something soothing to the patient while she wiped the patient’s tears. Once the patient was calmer, she unfolded a warm blanket over patient’s chest and outstretched arms while rubbing the patient’s arms like a loving mother would to a sleepless child. The patient slowly closed her eyes and drifted asleep.

Reflecting back as a medical student now, the powerful imagery I witnessed that day is still seared to my brain: a physician’s gloved hand clasping the outstretched patient’s hand. It was such a simple, but meaningful gesture of the physician’s compassion toward the frightened patient. As physicians, we are privileged to serve patients when they need us most. Often times, that may mean encountering patients on some of their most difficult, challenging, or life-changing moments. Although the attending anesthesiologist has undoubtedly encountered many D&C procedures in her lifetime of work, I admired how in tune she remained to the patient and her needs. She recognized how difficult this operation was for the patient and provided a hand to hold and soothing words when the patient was most vulnerable.

Within the career of medicine, we are long-standing witnesses to the great highs and lows of life. Physicians are not only healers of the body, but of the mind and soul as well. Never must this work become so routine that we lose sight of humanity in our daily efforts. Never must we forget to hold our fellow brother or sister’s hand.

Created by: Jessica Priestley

Created by: Jessica Priestley

The theme of my creative project for this course was “the art and science of medicine” – a concept that has made an enormous impact on both how I envision my career as a physician, and the relationships I will have with my patients.

The base of my project are two cardboard letters – M and D. Those letter reflect both the culmination of a dream to come to (and complete) medical school, and the commencement of a career. More than that, I believe that the M.D. degree represents a part of both who I am and who I want to be. The degree represents a tremendous amount of hard work for me, personally. However, and more importantly, it signifies the special trust placed in medical professionals by the public. It signifies the type of person who dedicates her life to the service of others.

I’ve drawn certain steps in the organizational hierarchy of life on each face of the two letters. Starting on one face of the “M,” there is a single cell with its various organelles: a nucleus in the center with its nucleolus and nuclear pores, surrounded to one side by rough endoplasmic reticulum. The functions of that cell are integral to the functioning of the tissue, organ, and organism as a whole. As a result, a great deal of medical attention is paid to the cellular level of a patient – from specific receptor blockers to chemotherapeutics that inhibit transcription, we rely on our ability to manipulate cellular function in order to treat disease in a whole patient. However, it’s not enough for physicians to spend their time thinking about cells and organelles.

On the first face of the “D” is a histological depiction of nervous tissue, featuring axons branching away from a neuronal cell body and nearby glial cells. Physicians must expand their consideration of disease and health to consider the function of tissues that cells comprise. I picked nervous tissue because I think it nicely illustrates the fact that one cannot focus too heavily on a single cell type (neurons, for example) without considering the role of “supporting” cells (glia, for example). Historically, the scientific world has put a lot of energy into studying neurons because they seem synonymous with nervous tissue. Today, we are learning more and more about the critical role glial cells play in the function and dysfunction of the nervous system.

Turning over the “D,” I’ve drawn a coronal section of a brain, the whole organ comprised by nervous tissue. To this point, my illustrations have dealt with the basic science of medicine – the cellular biology, histology, anatomy, and physiology. That information is the foundation of our eventual medical practice – this is the science of medicine.

The art of medicine is less tangible, and is represented both by my depiction of the cell, tissue, and brain as caricatures of the “real thing,” as well as by my abstraction on the flip side of the “M.” Accompanying the illustration are the three virtues (courage, humility and mercy) and six professional responsibilities (compassion, competence, honesty, professional responsibility, respect, and social responsibility) from the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine “Virtuous Professional” document. Each of those qualities contribute to the skill of practicing the “art of medicine,” which to me means the ability for a physician to relate and respond to a patient’s needs as both a collection of cells, tissues, and organs, and as a living, feeling human being with medical needs that will surely traverse the divide between biology, psychology, and sociology. While cells, tissues, and organ systems represent “doctor-centered-ness,” these qualities are what comprise “patient-centered-ness” and solidify the physician-patient relationship as more meaningful and significant than a simple business transaction. We spent some time in class talking about those values in a very black-and-white sense, as if they are easily attained and acquired after an hour’s discussion. Instead, those words rest on a colorful background representing the richness of experiences that both we as physicians and our patients bring to the medical experience. These concepts are not clear cut, and will not always be easy. There will be mistakes, but there will (hopefully) also be growth from those mistakes.

Finally, my project has the physical quality of dimension (i.e. both sides of the letters), meant to underscore the complexities of the physician-patient relationship. Those complexities are multi-dimensional and include some themes from this course: a diverse patient population with unique cultural, ethnic, and religious beliefs about both wellness and illness, patient autonomy, fiduciary relationships and the dynamics of trust and power, and the flow of information as doctors inform their patients of options, risks, and rewards. It is that richness that I look forward to most as I advance through my training because it is what makes the illness of Mrs. Abernathy with heart failure a different challenge than Mr. Brown with heart failure, even though the molecular/cellular aspects of their shared disease might be quite similar.

Created by: Dan Roberts

Created by: Dan Roberts

As I descended into impassable rivers I no longer felt guided by the ferrymen…

_arthur rimbaud

A mandala (Sanskrit: ‘circle’) is a design, typically seen in Hindu and Buddhist contexts, symbolizing the universe. Tibetan Buddhist monks often use mandalas as a meditation tool, and Native American Indians and various groups use mandalas in rituals for healing. The Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung utilized mandalas with his patients, as he viewed the mandala as a tool to explore the human psyche.

So, as this project was intended to be reflective, my immediate thought was that I would utilize the mandala as part of my own reflective process. The center of my mandala represents my eye (my right eye has partial heterochromia) looking back at me—to remind me of my own vulnerabilities, as well as the importance of being aware of my own values, biases, etc., and the effect these programs can have on my future relationships with patients.

Prior to coming to medical school, I worked with clients struggling with mental distress, as well as addiction issues. I very much enjoyed working in this capacity, but felt that I needed to continue on with medical training, to allow me to better promote healing through a mind-body connection. As this moment, I foresee myself pursuing psychiatry, so that I can help individuals to navigate those impassible rivers to find their own inner healing (represented in my mandala by the dark black ring encompassing an inner array of color and light).

The doctor is effective only when he himself is affected. Only the wounded physician heals.

_carl jung

Created by: Felicia Nip

Created by: Felicia Nip

Each hand is a reminder that we, as future physicians, hold a power to lead and guide the health of our patients. But, hands are meant to give as much as they are meant to receive. Therefore, we must humbly allow our patients to guide us in using our powerful tools. Each hand is also a reminder to acknowledge diversity. We may understand our own capabilities, culture, experiences, and ideas, but we must also respect and attempt to understand both our colleagues’ and patients’ as well.

On display are hands from MSU CHM (M1) students. Every one of us will bring diverse cultural, educational, religious, and geographical experiences across Michigan communities in our third and fourth years. The challenge I pose for my peers, and myself is to think about what can, should, and will be accomplished with our hands each year. I believe each pair of hands can and will change innumerable lives. My goal as a future physician is to wear out my hands by serving others.

[facebook]

[retweet]

during labor. ACOG committee opinion No 295. American College of Obstetricians

during labor. ACOG committee opinion No 295. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

and Gynecologists . Obstet Gynecol 2004; 104: 213.

. Obstet Gynecol 2004; 104: 213. [Computer

[Computer program]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing

program]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing ; 2012.

; 2012. outcome in women with self-prepared birth plan. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2012; 25(10): 2055-7.

outcome in women with self-prepared birth plan. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2012; 25(10): 2055-7.